Learn about antiques and collectables...

Click on a category below to show all the entries for that category.

Learn about and understand the items, manufacturers, designers and periods as well as the specialist terms used in describing antiques and collectables. Either click one of the letters below to list the items beginning with that letter, or click on a category on the left side of the screen to list the items under that category.

Albany Pattern

The Albany pattern is a design of sterling silver cutlery (silverware) that was popular in the 19th century. It is characterized by a simple, elegant design with a plain handle and a pointed tip. The pattern is named after Albany, New York, where it was first produced by the firm of Rogers, Smith & Co. in the 1850s. The Albany pattern is considered a classic design and is still popular today. It is typically used for formal occasions and is often paired with fine china and crystal.

Albert Pattern

The Albert pattern is a decorative design that was popular on sterling silver cutlery in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It is named after Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, who was known for his love of art and design. The Albert pattern features a series of scrolls that terminate in foliate motifs, that are etched or engraved into the surface of the silver. It is typically found on knives, forks, and spoons, and is often used in formal or special occasion settings.

Angell Family of Silversmiths

There were a number of members of the Angell family who were silversmiths, commencing with Joseph Angell I (also expressed as Joseph Angell, Senior), and his brothers John Angell and Abraham Angell.

On the retirement of Joseph Angell I in 1948, from what had become the leading London silverware workshop, the business was taken over by his son, Joseph Angell II (also expressed as Joseph Angell, Junior), (1815 - 1891).

Joseph Angell II exhibited at the at the 1851 Great Exhibition, the 1853 New York Exhibition, and the 1862 International Exhibition winning medals at each event.

His career is marked by the rich silver items crafted and decorated with chiseling, reliefs and enamels, including trays, tea and coffee sets, jugs, centrepieces and vases

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London holds a number of silver objects by Jospeh Angell II.

Apostle Spoon

Spoons, originally made both in sets of 13 and singly, that have as the finial a cast figure in-the-round, depicting one of the twelve apostles or Christ in Majesty, with his emblem. Apostle spoons were popular in England and Germany in pre-Reformation times.

Complete sets of thirteen different silver apostle spoons having the same maker and date, and dating from the 16th century are extremely rare, and even single apostle spoons of this period fetch a high price.

Apostle spoons have been reproduced in great numbers and those from the 19th century onwards often show the figure without an emblem, and are comparitively cheap to purchase.

Argyle

The argyle, also spelt argyll, is late 18th century gravy container with a spout, used to keep gravy warm. It has an outer container usually with its own outlet into which hot water is poured, whilst the inner container holds the gravy. Usually of silver or Sheffield plate and said to have been designed by the Duke of Argyll.

They were popular between 1760 and 1820.

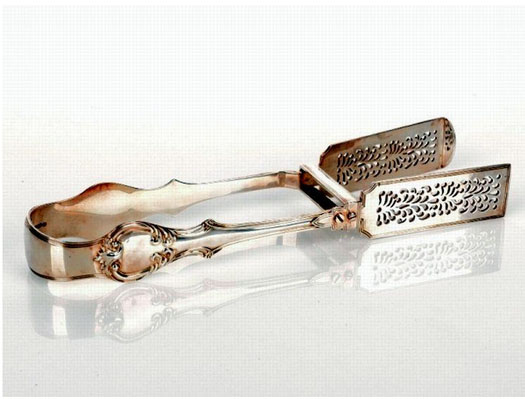

Asparagus Tongs

As the name indicates, these were tongs designed for serving asparagus. They were in use from around 1780 to 1830. and over that time the design evolved. The earliest form had a sppring jaw with a number of small concave ridges along the inner face, for holding the asparagus spears. Later examples had a tong action with pireced decoration, or a pair of rounded holders for gripping the circular stems of the asparagus.

Baskets - Silver

Although we have separate categories for various types of silver baskets according to their catalogue description - bon-bon, bread, cake, fruit, sugar and other unspecified - these baskets were variable in their uses.

They were made in a variety of shapes including circular, oval, and rectangular, mostly with a swing handle and sides pierced with geometric or scrolling shapes. Some have four feet while others stand on a rim.

Basting Spoons

A long handled spoon, usually 30 to 35 cm long, for scooping up the meat juices in the bottom of the roasting vessel, and pouring them over the meat, to ensure the meat browned as it cooked.

Basting spoons date from the 17th century, and the early examples had a tubular tapering handle (to facilitate cooling of the handle) and a spherical end cap. However few early examples survive, as the handles easily dented or fractured and were difficult to repair.

Later examples from about 1770 to 1860 had a conventional flat handle as seen on other types of spoons of this period.

Bonbonniere

A small elaborate lidded container for holding sweets (bon bons) used in the 18th century and 19th century. Most commonly they were circular in shape, about 6 to 9 cm in diameter and 2 or 3 cm high. However other shapes such as egg, rectangular and a circular legged bowl are seen.

Generally expensive materials were used in their manufacture including gold and silver, enamel, tortoiseshell, ceramics and minerals such as nephrite, bowenite, rock crystal.

To illustrate the prices at the top end of the market, Christie's London in 2004 sold a Saxon hardstone and gold bonbonniere inlaid with 57 numbered specimens of hardstones including a variety of dendritic and banded agates, By Johann-Christian Neuber, Circa 1785/1790, for £265,250 (US$424,400 at the time). At the other end of the market, less expensive examples sold in London can fetch only £100 or £200.

A simpler variation in the 19th century were those in glass or ceramics, in the form of a footed bowl with a lid.

Very few bonbonnieres appear on the Australian market.

.

Boss

A boss is small round or oval decorative device, used as ornament in Neo-classical style furniture, ceramics, sculpture and other decorative arts. They are usually applied to the surface in the form of stylized rosettes, but in the best pieces they are carved directly into the surface. Also known as paterae (or patera) or rosettes.

Brandy Warmer

A brandy warmer is a decorative container, traditionally made of silver, used to heat and serve brandy. The container typically has a handle, a spout for pouring, and a removable lid, and it's designed to keep the brandy warm and to enhance the flavours and aromas of the drink.

Brandy warmers were commonly used during the 19th century in Britain and America, especially in upper-class society. Many of these warmers were made of silver, as it was an expensive material that symbolized wealth and luxury. They were often used as a serving piece during formal meals, and were also used for special occasions like Christmas or New Year's celebrations.

The design of these warmers vary. Some were simple and plain and others were more elaborate with intricate engravings or other decorative details. They were made by different silversmiths and manufacturers and can be found in different styles and sizes, varying from the traditional and classical to the more modern and bold designs.

Britannia Standard

A higher grade of silver than sterling silver. Britannia standard silver contains at least 958 parts per thousand of pure silver, while sterling silver contains at least 925 parts per thousand of pure silver.

The Britannia standard was obligatory in Britain between 1697 and 1720 and after that was optional, so there are very few silver items that come onto the market that are Britannia standard.

Not to be confused with silver plated Britannia metal items, often marked as "EPBM", a pewter type alloy, that when unplated can be temporarily polished to a silver-like lustre.

Caddy Spoon

A caddy spoon is a short handled spoon used for measuring the dried tea from the tea caddy, where it was stored, to the teapot, and most commonly in use from the late 1700's to the mid Victorian period, although examples continue turning up dated into the early 1900s.

Caddy spoons were produced in all shapes and forms ranging from traditional patterns of the 18th century to striking designs by artist craftsmen of the 1920s.

Arts and Crafts caddy spoons in particular show the widest range and diversity of style. At the turn of the 20th century established designers of the day put their own interpretation on traditional forms and caddy spoons were produced in silver, copper, brass and pewter.

They are recognized for their simple elegant shapes, hand-hammered finish and are often decorated with enamel or cabochon gemstones.

Caddy spoon collectors may concentrate on specific makers and their individual hallmarks, and enthusiasts are always looking for less prolific or unrecorded makers.

Cake Basket

Popularly known as a cake basket, these baskets were probably also used for bread and fruit. They were introduced between 1730 and 1750, and at this time were usually oval in shape. Most cake baskets have a swing handle and pierced body. On important examples, the bottoms are engraved with armorials. Their popularity continued until the third quarter of the 19th century. Although oval shapes continued to be made, there were variations introduced and the designs became more flamboyant.

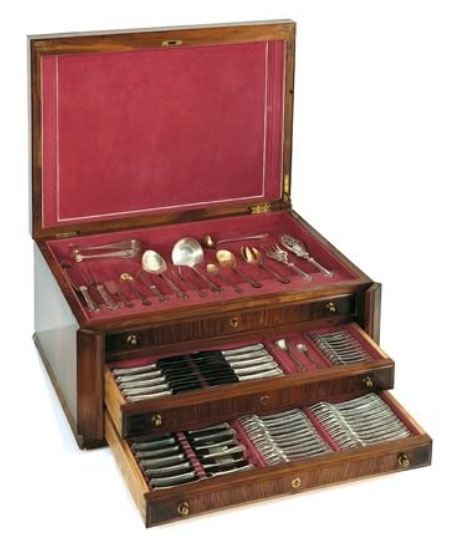

Canteen

A small cabinet, table or a box with drawers or lift out trays, for storing a set of cutlery.

Caster

Casters are so-called because they ‘cast’ their contents over food. They consist of a container, usually in silver or pewter with a removable perforated top which allows for the sprinkling of condiments such as sugar, pepper and nutmeg.

Caudle

Caudle is a type of warm, sweet drink typically made from a mixture of wine or ale, sugar, and spices. It was popular in medieval Europe, especially in England, and was often served to sick or convalescent people as a form of nourishment. the drink was also served at special occasions such as births, christenings, and weddings. The drink would be poured into a large bowl and guests would be served from it using a ladle, or it would be served in caudle cups, made of silver or pottery with a lift off lid.

Cellini Pattern or Style

Cellini pattern or style refers to the decoration of silverware characterized by ornate, highly detailed designs. These designs often feature figures, animals, and other decorative elements that are inspired by classical mythology and the natural world. The ewers and jugs are usually made of silver and are often decorated with intricate engraving, repoussé, and chasing.

The style is named after Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571), a famous Italian goldsmith, sculptor and artist of the Renaissance period. Cellini's work was known for its intricate designs, which were often inspired by classical mythology and the natural world.

They are considered to be highly decorative, high-quality pieces that are appreciated by collectors and connoisseurs.

The Cellini style is considered a very high form of metalworking, it's very detail oriented and requires high skills, craftsmanship and time. It's usually found in high-end and luxury pieces and is often seen as symbol of status and wealth.

Chafing Dish

A chafing dish is a type of portable heated tray or stand that is used to keep food warm during a meal or event. It is typically made of metal or stainless steel and has a shallow tray or pan for holding the food.

The tray is usually placed on top of a fuel burner, which generates heat to keep the food warm. Some chafing dishes also have a cover or lid to help retain heat and prevent contamination. Chafing dishes are often used at buffets, banquets, and other events where food is served and may need to be kept warm for an extended period of time.

Chalice

A chalice is a large cup or goblet that is used in religious ceremonies, particularly in Christian liturgical traditions. It is typically made of precious metal such as gold or silver, and is used to hold wine during the Eucharist, which is the central sacrament of the Christian Church. The chalice is also called the "cup of salvation" and is a symbol of Jesus' sacrifice on the cross.

In the Christian tradition, the chalice is a symbol of the blood of Jesus Christ, which is offered to the faithful as a means of grace and salvation. The chalice is used to hold the wine that is consecrated during the Eucharist and is considered to be a sacred object.

In the liturgical celebration of the Eucharist, it's passed around to the faithful, and the believer drinks from it to partake in the sacrament. Chalices are also used in other liturgical celebrations such as baptism, confirmation and anointing of the sick.

Chalices come in different shapes and sizes, from simple cups to highly ornate and decorative vessels, some of them are adorned with precious stones and intricate engravings. Chalices can also be used for other purposes, such as for holding holy water for baptism, or for the distribution of ashes on Ash Wednesday.

Chasing

The method of decorating gold and silver objects using a punch and hammer so that the design appears in relief. Flat or surface chasing is done from the front giving the item definition, but not cutting into the metal.

Chasing is the opposite technique to repousse, but an object that has repousse work, may then have chasing applied to create a finished piece.

Chatelaine

Originating in the 17th century as a device for suspending seals, by the late 18th century the chatelaine had evolved to become a major item of jewellery, worn from the waist, to which a variety of small implements, cases, and containers could be attached.

It took the form of a metal shield or plate fitted with a hook at the top to attach it to a belt, with a number of hooks at the bottom from which hung a number of short chains.

The objects attached to those chains covered the full gamut of household and personal activities and depending on the station of the wearer, could typically include about 4 to 6 from the following selection: sewing scissors, a scent bottle, keys, a spectacles case, a seal, a sovereign case, a vinaigrette, a vesta case, a pin holder, a snuff bottle, a tape measure, a thimble and a notebook.

Again depending on the station of the wearer , materials used included gold, sterling silver and silverplate.

Nowadays it is common for single items from the chatelaine to come onto the market.

Chocolate Pot

In 1521, during the conquest of Mexico, the Spanish conquistadors discovered cacao seeds, from which cocoa and cocoa butter, the basis for chocolate, are extracted. They took them back home to Spain, where new recipes were developed. About 100 years later, the drink spread throughout Europe and the Europeans began adding sugar and cream to their hot chocolate.

Chocolate pots were popular between about 1700 and 1800, and in style similar to a coffee pot , except that they included a small additonal secondary lid attached to the main lid, so that a rod called a molinet could be inserted into the pot to stir the chocolate before pouring. The handle is often set at right angles to the spout to facilitate pouring, and like a tea or coffee pot, may be insulated from the body of the pot.

Coaster

Coasters were intended to hold bottles or decanters of wine at the dinner table, and act as a recepticle to cash drips and ribbles on the foot of the wine container. As wine contains achohol, and residual liquid remaining on the base could damage the top of the table, more so if the table had a French polished surface. if the table had a cloth, the wine could leave a permanent stain.

On a table without a cloth, the felt base also allowed them to be slid from one guest to the next along the top of the table.

Made of silver or silverplate, they usually have a turned hardwood base, sometimes with a central silver boss, and usually covered in green baize on bottom.

The sides are usually cast or pierced, often with vine leaves, grapes and tendrils incororated into the design.

It is quite common for them to be available in pairs

Coconut Cups

Possibly one of the earliest types of cups standing on a stem or base, coconut cups are formed from the shell of the coconut, with a silver rim, and silver stem and foot, or multiple feet.

They were fashionable rarities in Western Europe in the late 15th century and throughout the 16th century. They again became fashionable in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, which is the period of those coming onto the market at the present time.

Comport

A comport is a type of decorative serving dish or bowl, typically used for desserts, fruits or other sweet treats. The comport is usually made from glass, silver or porcelain, which are materials known for their elegance and durability. They are often beautifully designed and decorated, and can be used as an elegant and decorative centerpiece for a table or dining room. They are also widely used as a decorative piece on the mantelpiece, sideboard, or other areas of the house.

Cream Jugs

The cream jug or milk jug was a component of most 18th and 19th century tea and coffee sets, but the numbers coming onto the market as single units, easily outnumber those being sold as part of a setting.

Silver cream jugs first appeared around 1700 as tea was becoming popular, following its introduction to Europe by the East India Company. The major ceramics manufacturers, such as Royal Doulton, Royal Crown Derby, Shelley, Royal Winton and Wedgwood all included a cream jug with their dinner and tea ware settings. Small jugs made by individual craftsman potters have also been labelled cream jugs, probably being the name most suitable for the size and style of the vessel.

Cream and milk jugs mostly have a pitcher shape, with a wide pouring spout and a baluster foot or three legs.

Crimped

A wavy effect on the the rims or lips of glass or silver vessels. Crimping was frequently used on brightly coloured Victorian glass.

Cruet and Condiment and Sets

A cruet also known as a caster, is a small container to hold condiments such as oil, vinegar, mustard, pepper. Its shape and adornments will depend on the specific condiment for which it is designed. For example a cruet for liquids may have a jug-like shape, while a cruet for a spice may be cylindrical with a lid and perhaps a small spoon for serving.

Cruets were made in silver, silver plate, ceramic and glass, and sometimes a combination of two materials, usually as a glass body with a silver or silver plated top.

The earliest cruets, from the beginning of the 18th century were known as "Warwick cruets" after a cruet set made by Anthony Nelme in 1715 for the Duke of Warwick, and include three elaborately decorated and shaped matching silver casters, usually with one unpierced, which held powdered mustard, and the other two for oil and vinegar, combined in a stand with a handle enabling it to be passed between dinner guests.

In the Victorian era with more elaborate dining settings, the number of condiments used during a meal increased, as did the number of containers in the cruet set, and some cruet sets contained up to six or eight containers, either arranged tw-by-two, or in a circular container. Glass bottles replaced the silver containers of the earlier era and the holders became simpler, sometimes being a metal frame attached to the base.

Completeness and originality is important when purchasing a cruet set, and missing containers, replaced containers and missing or chipped stoppers will depreciate the value of a cruet set.

Another type of cruet set is an egg cruet, typically consisting of four to eight egg cups in a stand, often with a spoon for each egg cup. These were mainly made in silver or silver plate, and occasionally ceramic. The egg cups may fit in rings, or over a stud on the base of the stand. Sometimes the interiors of the egg cups are gilded to prevent corrosion. The stands are either solid, or a framework with a handle.

Date Letter on Silver

A date letter is a letter or symbol that is used to mark silver and other precious metals to indicate the year in which the piece was made. The date letter system is used by the British hallmarking system and it is a way to verify that a piece of silver is genuine and has been assayed (tested) by an official assay office.

The date letter system has been in use since the 14th century and it changes every year, so it is possible to identify the year in which a piece of silver was made by looking at the date letter. The date letter is usually stamped alongside other hallmarks such as the maker's mark, and the standard mark (indicating the fineness of the metal) on the silver piece. The style of the letters varies depending on the assay office, and the style of the lettering also changes over time. The date letter is usually placed inside a shield shape, sometimes accompanied by other symbols.

The date letter system is not used in all countries, so if a piece of silver does not have a date letter, it does not necessarily mean it is not authentic. The date letter system is not always used for small or insignificant silver items.

Devlin Stuart

Stuart Devlin was born in Geelong, Victoria, Australia and trained as an art teacher, after which he taught for 5 years and then studied gold and silversmithing, firstly in Melbourne and then at the Royal College of Art in London from 1958. He spent two years at Columbia University where he developed a career as a sculptor.

He returned to his teaching position in Melbourne in 1962 and was appointed Inspector of Art Schools.

In 1963 a competition was held to design the new Australian decimal coinage that was to be introduced in 1966. The new decimal coins were to replace the pre decimal coinage that had been in circulation since 1910. Six competitors vied for the honour of designing these new coins.

Devlin was announced the winner of the competition with designs that featured Australian native fauna on the new coins, with the 1c coin featuring the feather-tailed glider, the 2c a frilled neck dragon lizard, 5c a spiny echidna, the 10c a lyrebird, the 20c duck billed platypus and the 50c Australian Coat of Arms. The 1,c and 2c coins are no longer in circulation. A $1 coin also designed by Devlin and featuring the kangaroo, was introduced in 1984

In 1963 He became involved in the project to design Australia's decimal currency, and during this period he decided to relocate to London and establish himself as a silversmith.

He adapted his knowledge of sculpture into the designs he created for his showroom in Conduit Street in London's West End, which he occupied from 1979 to 1985. His output included limited editions which appealed to longer term collectors, such as Easter eggs and Christmas boxes.

His design skills have extended to furniture, jewellery, clocks, centrepieces, goblets, candelabra, bowls, and insignia.

Following his successful design on Australia's decimal currency, he has designed coins and medals for 36 countries.

He was Prime Warden of the Goldsmith's Company 1996-97 and in 1982 was appointed as goldsmith and jeweller to Queen Elizabeth II and in 1998 he was appointed a member of the Royal Mint Advisory Committee on the Designs of Coins, Medals, Seals and Decorations.

In 2000 he designed 25 coins for the Sydney Olympic Games including the Silver Kilo Olympic Masterpiece, the largest Olympic coin ever made, and the first to show all Olympic sports. He was also awarded an honorary doctorate from RMIT in 2000.

His work is displayed in the Victoria and Albert Museum as well as numerous Australian museums including Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, Museum Victoria and the National Gallery of Victoria.

He was awarded a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George in the UK in 1980, and an Order of Australia in 1988.

Dick, Alexander

Alexander Dick (c.1791-1843) arrived in Sydney as a free-settler from Edinburgh in 1824 and employed a number of assigned convicts in his workshop.

Probably initially employed by James Robertson, Sydney's first non-convict silver retailer and also from Scotland, Dick soon established his own business at 104 Pitt Street as both a retailer and working silversmith.

Although himself sentenced in 1829 to seven years transportation to Norfolk Island for receiving stolen dessert spoons, he was later pardoned and returned to Sydney.

For the next ten years his firm, received many significant commissions and became one of the most prolific manufacturers of silver flatware and presentation pieces in the colony.

His mark appears on the first Australian-made racing trophy (the 1827 Junius Cup) and he was praised as the maker of the Sydney Subscription Cup, a now lost 84oz silver trophy ornamented with a gold horse finial and gold horse-heads for an 1834 race meeting.

Retiring in 1841 (the year the first silver mine opened in Australia), he died two years later leaving an estate of almost £9000.

Dish Rings

Dish rings were in use between about 1750 and 1800, and were designed to protect the table or sideboard surface from damage from a hot dish. They are usually about were mosty made in silver, and to a lesser extent Sheffield plate, of circular in shape with pierced, embossed and chased decoration to the in-curved side, the piercing also allowing the heat to escape.

They are also known as potato rings, probably in deference to their supposed Irish origins.

Manufacture of dish rings was revived in the late 19th century for several decades.

Edward Fischer

Edward Fischer (1828-1911) migrated to Australia from Vienna in the early 1850s, and settled into business as a jeweller in Geelong, which at that time was an important commercial centre particularly for the export of wool. It was a very prosperous centre attracting many watchmakers and jewellers, as no doubt there were many well-to-do clients.

Fischer was an important jeweller in the town, producing outstanding quality silver and gold wares, indeed, he was commissioned to manufacture the first locally produced Melbourne Cup, and became well known for his design and craftsmanship in producing the Geelong Racing Clubs presentation cups from 1873 to 1890. He was also a quality producer of silverware for Kilpatrick & Co. and Walsh Bros. of Melbourne.

In 1891 Fischer sold his business and left Geelong, relocating to Collins Street, Melbourne, where he traded as E. Fischer and Son, Manufacturing Jewellers, Watchmakers and Opticians. Apparently the business was managed by his son Harry. Edward Fischer died in 1911, but the business continued until about 1916.

Jewellery by Fischer is marked FISCHER or E. FISCHER, GEELONG.

Elkington & Co.

Elkington & Co. was a Birmingham silverware company producing fine silverware and silver plate. The business was founded in 1815, by the uncle of George Richards Elkington (1801-65). On his uncle's death George Richards Elkington became the sole proprietor and took in his brother Henry Elkington as a partner, changing the name to G. R. Elkington & Co. The business took out patents for the plating of articles in 1836, 1838 and 1840. In 1842 a third partner, Josiah Mason, joined the firm and the name was changed to Elkington, Mason, & Co. until 1861, when the partnership with Mason was terminated.

The greater durability of electroplate together with its affordability meant that it steadily ousted pure silverware, especially for the more functional items such as tea and coffee services. The company licenced the process to a number of manufacturers, including Christofle & Cie of France.

By 1880 the company employed over 1000 workers at premises in Birmingham, and had a further 6 works.

The company received awards at the great international exhibitions from the 1850s onwards for its excellence in artistic quality and fine design and held Royal Warrants from British Royalty including Queen Victoria, King Edward VII, Queen Alexandra, King George V, Queen Mary and King George VI. Elkington & Co. supplied plated wares to the luxury dining sections on board the Titanic and other ships in the White Star Line fleet.

By 1900 the Elkington monopoly of electroplate diminished as the original patent rights expired, and this period witnessed the enormous increase in output of other Birmingham, London and Sheffield manufacturers.

The firm operated as Elkington & Co. from 1861 until 1963 when it was acquired by British Silverware Ltd. which also had the Mappin & Webb brand. During World War II the company had stopped producing plated wares, and moved into copper refining which continued when it became a subsidiary of Delta Metals Group in 1955.

The original Elkington Silver Electroplating Works, in Newhall Street in Birmingham, became the Birmingham Science Museum in 1951, until its closure in 1997.

Engraving

The method of decorating or creating inscriptions on silver and other metal objects by marking the surface with a sharp instrument such as a diamond point or rotating cutting wheel.

Entree Dishes

The name would indicate that entree dishes were designed to serve the course before the main course.

However they are also called "serving dishes" which is probably more indicative of their purpose: to hold and serve the vegetables accompanying the meat, or to hold the hot accompaniments for a breakfast. In order to keep the contents of the dish warm, many entree dishes had an inlet and double skinned base so that hot water could be added to the lower section of the dish. Another feature of theses dishes is the detachable top handle, allowing the dish itself to be heated in the oven or on the stove, with the unheated handle added after the hot dish was removed from the heat.

They became popular in the late 18th century, and were often made in pairs or fours. When owned by an important family, the family's armourials were often engraved on the lid.

Epergne

A table centrepiece, which may have a large central bowl or dish, and a series of smaller bowls suspended from a central stem or branches, with the smaller bowls used to display sweetmeats. Some of the grander examples were made in silver, but epergnes were also made in ceramic and glass.

Feather Edge

A feather edge on a silver item refers to a decorative border that is created by using a series of thin, closely spaced lines that resemble the feathers of a bird. The feather edge design, first applied in Britain circa 1765, is often applied to the edges or rims of silver plates, bowls, or other hollow ware to create a decorative border. It's a common design element in antique and vintage silver items and is also used on modern pieces. The feather edge is created by hand, using a specialized tool called a burin, and is often combined with other decorative elements, such as engraving or chasing, to create a unique and ornate design.

Fish Servers and Slices

The fish slice dates from about the 1750s, and was popular until the late Victorian period. made of silver or silver plate, they were designed for serving fish at the table, and usually had a wide scimitar shaped blade, often pierced and engraved with a flat or decorative cast handle.

Some fish slices had a marine decoration to the blade or handle representing fish, eels or shrimps.

During the Victorian period, they were popular as a gift presented in a boxed set with the addition of a wide bladed matching fork, and were then called fish servers.

Hallmarks

A mark stamped on articles of precious metals in Britain, since the 14th century, certifying their purity. It derives its name from the Guild Hall of the Goldsmiths' Company, who recieved its Charter in 1327 giving it the power to assay (test the purity) and mark articles of gold and silver.

The hallmark will consist of several marks, including the:

- silver standard mark, indicating the purity of the metal. Sterling silver is .925 pure silver.

- the city mark indicating the city in which it was assayed eg London, Birmingham, York etc.

- the date mark, usually a letter of the alphabet in a particular font and case,

- a duty mark, indicating whether duty had been paid to the crown, and only in use from 1784 to 1890

The piece may include an additional mark, the maker's mark, although not forming part of the hallmark, will be located in the vicinity of the hallmarks.

Sometimes silver plated items will bear faux hallmarks, often confusing those not familiar with silver markings.

Hanoverian Pattern

This style was popular under George I, between 1700 and about 1770, and was characterised a simple form consisting of a long bowl and central spine running up the face of the spoon, with the handle widening towards the top, and the end of the spoon curving upwards instead of downwards as with most patterns.

Production of spoons and forks in the Hanoverian style was revived in the 19th century.

Hmss / Hms / Hm

An abbreviation for "hallmarked sterling silver".

Husk Motif

The husk motif is a decorative element that has been used in furniture, silver, glass and ceramics decoration for centuries. The motif is typically based on the shape of the husk, or outer covering, of a nut or seed. It is often depicted as a series of overlapping, scalloped shells that create a textured, ornamental pattern.

In furniture, the husk motif is commonly used in the design of chair and table legs, as well as in the decoration of cabinet doors and drawer fronts. The motif is carved into the wood or other material, creating a three-dimensional effect that adds depth and visual interest to the piece.

In ceramics, the husk motif is used in a variety of ways, from the decoration of bowls and plates to the design of decorative tiles and other objects. The motif is often painted or carved into the surface of the clay, creating a relief pattern that adds texture and dimensionality to the piece.

The husk motif has been used in many different historical and cultural contexts, from ancient Greece and Rome to 18th-century France and England. It has been adapted and modified over time, with variations including the acanthus leaf and the palmette motif.

Joachim Matthias Wendt

In many respects the history of Wendt's is a potted history of Australian gold and silver smithing. State directories of the late 1800s show that they sold watches, jewellery, rings, trophies, church plate, optical goods and electroplate. They also repaired watches and jewellery.

Joachim Matthias Wendt arrived in Port Adelaide in 1854, just 18 years after the foundation of South Australia. He was born in 1830 in Denmark. His mother died when he was nine years of age, leaving his father to look after him and two sisters. Joachim became a watchmaker's apprentice.

He brought these skills to South Australia, quickly opening a small watchmaking and jewellery shop in Pirie Street, Adelaide. Business was good and so he soon moved to better premises in Rundle Street.

Wendt's soon became recognised as a top quality shop. The jewellery, silverware, watches and clocks were equal to the best which were imported. In 1864 and 1865 Joachim received first prizes at a Scottish exhibition. In 1871, Wendt's was selected to make silverware caskets featuring Australian motifs for the Duke of Edinburgh, who was visiting Adelaide and other towns.

So pleased was the Duke of Edinburgh with Wendt's craftsmanship that he purchased additional items and appointed J. M. Wendt 'Jeweller to His Royal Highness in this Colony', By this time, twelve silversmiths, watchmakers, jewellers and shop assistants were being employed. What could not be made locally was imported.

Wendt's reputation for quality was further confirmed by the award of two first prizes for silverware at the 1878 Paris Exhibition. Success followed success, leading to a broadening of interests, including an involvement in the building of the Theatre Royal, the Adelaide Arcade and the Freemason's Hall.

J. M. Wendt had married a widow, Johiamic Koeppen, in 1872. Her son Herman entered her husband's jewellery business and added Wendt to his name, becoming Herman Koeppen (H. K. J Wendt. He and his brother, Jule, in 1903 were made partners of the business, Jule was sent abroad to be the overseas buyer.

Joachim Wendt died in 1917 aged 87. Nonetheless, the business continued to flourish under H. K. Wendt's management. His eldest son, Alan, joined the business in 1919, becoming a partner. On his father's death in 1938, Alan became sole proprietor. In 1947, Alan's son Peter Koeppen Wendt, joined his father and they became the first directors of the newly formed private company.

The final managing director of J. M. Wendt's was Timothy Wendt. Five generations of the family held executive positions in the business until its closure at the end of the 20th-century.

A highlight in Wendt's long and successful history was to be commissioned by the South Australian Government to manufacture a necklace and ear-rings for Queen Elizabeth II, and cuff links for the Duke of Edinburgh, for their visit in 1954. The jewellery had to incorporate opals, the most magnificent of which was the 203 carat 'Andamooka' white opal owned by the Government. Palladium was chosen as the metal and the large opal was flanked by 180 diamonds. The necklace and earrings are illustrated.

A trade journal described the gift as follows: 'The opal and diamond necklet and ear-rings suite is mounted in jewellery palladium with the large opal as the centre of the necklet. This is flanked by elegant side pieces, hand-carved in an attractive scroll design handset with diamonds. The chain at the back is of diamonds, each set in a diamond-shaped setting alternating with links pierced in the matching scroll designs and finished with a diamond set snap.'

As Wendt's centenary year official history closed 'In this way Wendt's first hundred years were fittingly symbolised'. Alas, Wendt's has now closed

From: Carter's "Collecting Australiana", William & Dorothy Hall, published by John Furphy Pty. Ltd. 2005

Kettles on Stand

Unlike the utilitarian copper kettles found in the kitchen, these fancy kettles were an indispensable accessory for the formal tea party, held in the parlour or sitting room. Also known as spirit kettles, they were popular during the whole of the 18th and 19th centuries, and were originally used for replenishing the teapot.

They were sometimes one of the components of a tea set, but most examples appearing on the market in Australia are singles.

Most stands had four legs, with the burner situated at mid height between the four legs, allowing the presence or otherwise of a flame to be seen. Some kettles were attached to the stand with a chain, secured by a removable locking pin. The burners were removable from the frame for cleaning purposes

Knop (silver)

A knop on a silver item is either a bulbous protrusion mid way along a stem, such as on a candlestick or at the end of a stem, such as on a spoon, or a knob or finial on top of a cover or lid, that acts as a handle. On a stemmed item such as a candlestick there may be a series of knops of different shapes.

Linton Silver

The Linton's silver workshop in Perth was established early in the 20th century by James Walter Robert Linton. Born in Britain James Walter Robert Linton, was a trained painter and teacher of art, whose father was a practitioner and advocate for watercolour painting. James Walter Robert Linton came to Australia in 1896 to follow up an investment his father had made, and ending up staying. He taught art in Perth and returned to England in 1907-08 to study metalwork. On his return to Perth he went into partnership with another silversmith, Arthur Cross. On Cross' death in 1917, he was joined in the business by his son Jamie, who took over the running of the workshop. James Alexander Barrow Linton was born in Perth in 1904. Known as Jamie, he studied at the Perth Technical College and by 1921 was his fathers assistant in his silver smithing activities. He left Perth in 1926 to study in London and Paris. He returned to Perth in 1927 and worked with his father, eventually taking over the business and continuing the tradition of silver smithing. He died in 1980.

Loaded

In silverware the hollow part of the object, such as the stem of a candlestick or the handle of a knife, that has been filled (loaded) with pitch or sand to add additional weight for stability.

Marrow Scoops and Spoons

An item of cutlery used from the late 17th century, designed for extracting bone marrow from bone cavities after cooking. Bone marrow was considered a delicacy and at a time when cutlery was coming into use, a marrow scoop enabled a diner to extract the marrow with finesse, rather than sucking, slurping and mouthing the bones.

Some marrow scoops have a spoon like end, while others have a long narrow gulley end, and some are double ended with different size scoops at each end to suit various sized bones.

Marrow Spoon

A spoon with a long handle and a narrow scoop shaped bowl, used to scoop and eat marrow from the hollow centre of roasted bones. Some marrow scoops are double ended with a different shaped bowl at each end.

Meat Covers

Meat covers, also known as dish covers, were designed for covering large platters in order to protect the food and retain the heat. They are usually ovel, matching the typical shape of tha platter, and vary in size from about 30 cm to 60 cm. They are topped by a reeded or foliate handle. While the surface of most are solid metal, there are examples where the outer surface is wholly or partly plated wire mesh.

The covers were made in silver, Sheffield plate and silver plate and earlier silver examples date from the mid 1700s. Due to the amount of silver they contain, and consequently their cost, and value if sold for melt, silver covers are vastly outnumbered by plated examples. Sheffield plated examples date from the early 1800s while plated covers are generally from the Victorian era.

Monteith

A bowl with a scalloped or notched rim, used in 17th century to allow drinking glasses to hang by the foot into iced water for chilling before use.

Later examples often have a detachable rim, so the bowl can also be used for serving punch.

Mote Spoon

A mote spoon is a spoon with a perforated bowl, designed for removing floating tea-leaves from a cup of tea.

Muffineer

A muffineer is a

small container with a pierced top, usually of of silver, or silver plate. It gained

its name from its early use for sprinkling sugar or cinnamon on muffins. muffineer

were part of the Victorian tableware. After the First World War.

Noggin

A noggin is a small jug for measuring a gill of liquid (usually alcoholic spirits). In Imperial measures, a gill is equal to 5 fluid onces; in the US to 4 US fluid ounces.

Nutmeg Grater

With the rise of the British East India Company in the early 1600s spices of all kinds were imported into Britain from the Far East. One of these was nutmeg which as well as being an exotic flavouring for food, was also used for medicinal purposes (it was supposed to cure stomach ailments, headaches and fever), as an incense and as a fumigant.

The Dutch East India company had a monopoly on the import of nutmeg into Europe, and consequently it was a very expensive spice. The monopoly lasted until in 1769, a French horticulturalist smuggled some trees out of the Indonesian Banda islands, and soon after nutmeg trees were growing in Malaysia, Singapore India and the West Indies.

This enabled the monopoly of the Dutch to be broken, and the British East India Trading Company to import nutmeg into Britain. With supplies more plentiful, its use became more popular and from the late 1700s, nutmeg graters were produced for dispensing the nutmeg.

Due to the expense of nutmeg it was only affordable by the very wealthy, and as it had to be freshly ground, they carried a personal supply with them, and from about 1775, a nutmeg grater to dispense it.

The nutmeg had to be freshly grated to be efficacious, hence the development of the pocket sized nutmeg grater, which consisted of a small silver or turned wooden lidded box or cylinder, which, when the lid was opened displayed a grilled surface for grating with storage underneath for the grated nutmeg. It was soon realised that silver was too soft for this purpose, so blued steel grating surfaces were introduced.

Most nutmeg graters are silver, but they are also constructed around found objects such as Cowrie shells. Silver shapes include the acorn, walnut, cylinder and barrel, heart, urn and egg.

Very few nutmeg graters were made after 1850.

Old English Pattern

The Old English pattern as is commonly seen on silver flatware is characterized by a simple, clean shape with a slightly upturned tip and a broad handle that tapers gently towards the bowl or blade. The handle may be plain or decorated with a subtle design, such as a line or ridge along the edge or a small decorative motif at the tip. This pattern was first introduced in the 18th century and has remained popular ever since, making it a popular choice for traditional and formal table settings.

Onslow Pattern

The Onslow pattern is a design commonly found in silver and silver plated flatware. It is a highly decorative pattern that features a shell motif on the handle, which is often accompanied by scrolls, flowers, and other ornate designs. The Onslow pattern was first introduced in the mid-18th century and has remained a popular choice for flatware enthusiasts throughout the years. The design is named after Arthur Onslow, who served as the Speaker of the House of Commons in England from 1728 to 1761. It is said that Onslow was a great lover of fine silver and that the Onslow pattern was created in his honour.

Paul De Lamerie

Paul de Lamerie (1688-1751) was a highly skilled Huguenot silversmith, widely considered to be one of the greatest craftsmen of his time. He was born in the Netherlands in 1688, but his family fled to London in 1689 to escape persecution of Huguenots in France. His father was a watchmaker, and Paul began his training as an apprentice in his father's workshop.

At the age of 21, de Lamerie set up his own silversmithing workshop, where he produced some of the finest silverware of the 18th century. His work was highly sought after by the British aristocracy and European royalty. He was known for his exceptional technical skill, attention to detail, and ability to incorporate a range of decorative styles into his work, including Rococo, Baroque, and Neoclassical.

De Lamerie's creations included a wide range of objects, such as tea sets, candlesticks, salvers, tureens, and sauceboats, which were often decorated with intricate designs and chased or engraved patterns. He also produced large, ornate pieces, such as chandeliers and candelabra, which were highly prized for their beauty and technical skill.

In London, De Lamerie was a member of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths and was appointed as a silversmith to King George II in 1720. He was also a mentor to many apprentices, several of whom went on to become renowned silversmiths in their own right.

De Lamerie died in 1751, but his legacy lives on as one of the greatest silversmiths of his era, whose work is still celebrated for its exceptional beauty and technical skill.

Paul Storr

Paul Storr was the most prolific of the 19th century silversmiths, and was a master of the heavy neo-classical styles.

He went into business for himself after he completed his apprenticeship in 1796, and from 1807 was associated with the silversmithing firm of Rundell & Bridge, for whom he carried out many commissions.

He left Rundell & Bridge in 1819 and after a few years went into partnership with John Mortimer, trading as Storr & Mortimer which lasted until he retired in 1838 at the age of 68.

His workshop produced enormous quantities of silver and silver gilt in designs so heavy and robust that many objects have survived in excellent condition.

His patrons included both George II and the Prince Regent and his wares were highly sought after and remain so today.

Pistol Grip

Usually found on knives, and in use from about 1730, the pistol grip handle tapers out from the blade toward the end of the implement, and then curls in the shape of the truncated handle of an early pistol.

The grip is seen occasionally on forks, and also used to describe the handles on an urn where the handle rises up from the body of the urn towards the top, but turns down before meeting the neck, leaving a gap between the neck and the handle

Porringer

A small bowl or cup with or without a lid and a single or pair of flat handles, set horizontally, and traditionally was a bowl from which children were fed. The term is derived from the French 'potager', a vessel for pottage or stew. Porringers were made throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, in silver, pewter and delftware, and revived in the late 19th century. In America the term is used to describe a shallow, one-handled dish used for blood-letting.

Quaich

A quaich is a drinking cup, originating in the Scottish Highlands. It is in the form of a wide, shallow bowl and has two or three handles projecting from the upper section and sometimes has a circular foot. Small quaiches were for individual use, while the larger, ornate variety were used for communal drinking at ceremonies. The word quaich is derived from the Gaelic word cuach, meaning cup. A porringer is a similar vessel, but usually has only a single handle.

Rat Tail

A spoon with a flattened handle, tapering from the narrow section at the bowl, and wider as the top of the handle, that when viewed from above is of a similiar shape to a rat's tail. Also known as the Hanoverian pattern, as its manufacture spanned the reigns of George I, II and III (part) of the House of Hanover dynasty. The rat tail pattern was the forerunner to the Old English pattern.

Salver

A plate or tray used for the formal offering of food, drink, letters or visiting cards, usually of silver plate, silver or silver-gilt. Large, heavy, oblong or oval silver salvers evolved into what we know as trays in the 18th century. Small, flat salvers are known as waiters.

Sauce Boat

Sauce boats, also called gravy boats, are a small jug form object used for serving sauces and gravy as indicated by the name. They were made in silver, silver plate or ceramics became fashionable in the early 18th century. Early suaceboats were usually plain and of oval shape, with a solid oval foot.. In the later Georgian period they became more elaborate, with the metal examples decorated with chasing and engraving, and a three-footed base, and sometimes available in pairs. Ceramic suaceboats were often part of a dinner service, and some of the ceramic sauceboats have an attached plate, its purpose being to catch drips and dribbles.

Scallop / Shell Motif

The shell motif has been used in furniture and decorative arts for centuries. In ancient Greece and Rome, shells were often used as decorative elements on furniture and in mosaics. The scallop or cockleshell are the most commonly used. During the Renaissance, the shell motif became popular in furniture and architecture, as the ornate decoration was seen as a symbol of wealth and luxury. In the 18th century, the Rococo style of furniture and decorative arts featured an abundance of shell motifs, and it was used by Thomas Chippendale and as a feature on Queen Anne style cabriole legs. In the 19th century, the shell motif was incorporated into Victorian furniture and decorative items, and often a representation of the the conch shell was inlaid into furniture.

Silver Beakers

Usually of tapering cylindrical shape and without handles, silver beakers have been made from the 17th century onwards, but most examples appearing on the Australian market date from the mid Victorian period to the 20th century. They were popular as trophies for masculine sporting events.

Other shapes are the bell shape which has a flared top, and the half-barrel shape. Some beakers have embossed and/or chased decoration.

Silver Dredger

A silver table dredger is a small utensil used to sift through fine granulated sugar, salt or pepper, to remove any lumps or clumps before adding it to a dish. It typically has a small container, often with a handle, and a perforated or mesh bottom.

The dredger is used by holding it over a dish and shaking it to sprinkle the powdery substance through the holes or mesh. It can also be used to sprinkle powdered sugar over desserts such as cakes, pastries, and cookies, or to add a decorative touch to drinks like coffee and tea.

Snuffer

A device for extinguishing a candle, usually made of silver or silver plate, and sometimes ceramic.

There are two types, the first in the shape of a cone that is placed over the the top of candle and smothers the flame, also known as an extinguisher. The cone shaped snuffer may be part of a candlestick or have its own stand. The second type is similar to a pair of scissors with a small box on one of the blades into which the wick falls when it is cut.

Prior to the invention of snuffless candles in the 1820s, this type of snuffer was used to trim the wick of the tallow candles (also called "snuffing") that were in use at that time, so that they did not become too long. With the snuffles candle, the newly developed plaited wick bent into the flame as it burnt, and was fully consumed.

This type sometimes comes with an accompanying stand or tray.

However the two components may have been separated, and a new name found for the snuffer tray, such as a pen tray.

Stirrup Cups

Stirrup cups were for the pre-hunt drink, usually a port or sherry, offered to a member of the hunt mounted on horseback and about to depart for the hunt. As they were held in the hand they did not require a flat base Most of the cups are made of silver, although less expensive ceramic examples were also made, and they are usually in the form of a fox’s head or, more rarely, the head of a stag, greyhound or hare, or in the form of a hoof.

Most silver examples date from the early 1700s to mid 19th century. Many stirrup cups survive from the peak period of their production, the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and their popularity as collector’s items has led to their continued production by modern silversmiths.

Stokes (australasia) Ltd

Thomas Stokes a diesinker and electroplater was born in Birmingham in 1831, and arrived in Victoria in the 1850s, to join the search for gold. Soon after, presumably being unsuccessful in his quest or gold he established a business in Melbourne as a “Die Sinker and Medallist, Stamper and Token Maker”, and soon after added electroplating to the services he was able to supply.

By the 1880s he was employing 30 tradesmen and apprentices. The company's specialty was badges and at about this time they were producing coat and collar badges for schools, colleges, lodges and associations, the Victorian Railways, Salvation Army and the Australian Army. The business became a proprietary concern in 1911, re-named Stokes & Son Pty Ltd., and in 1962 Stokes became a public company, renamed Stokes (Australasia) Ltd

In the 1950s the company diversified into manufacturing components for the automotive and domestic appliance industries, and became one of Australia's leading suppliers to these industries.

Today, Stokes is a publicly listed company, with offices and representatives throughout Australia, Asia and the Pacific. As well as being the Australia's leading independent distributor of appliance spare parts, the industry leader in the supply of badges, medallions and associated products it is also the country's major manufacturer of electrical elements.

Tankard

A tankard is a drinking vessel for beer, ale, and cider, similar in shape to a large mug, and usually with a hinged lid. Silver tankards were in use in Britain and other parts of Europe from at least the sixteenth century, pewter tankards probably from the thirteenth. In the 19th century a number of ornately carved ivory tankards were produced, but these were designed to demonstrate the skill of the carver, rather than for day to day use. The shapes of tankards vary, sometimes globular, sometimes a tapering concave. For those with lids, the lid usually includes a thumbpiece that the drinker can hold down to keep the lid open. Variation in the design of the thumbpiece include wedge, ball and wedge, ball, hammer head, bud and wedge, double volute (scroll), chair-back, ball and bar, shell, double acorn, corkscrew, and ram's horn.

Tazza

A tazza is a shallow saucer-like dish, either mounted on a stem and foot, or on a foot alone, used for drinking or serving small items of food. The word is derived from the Italian for "cup", plural tazze. Tazza are usually found in silver, ceramics or glass.

Trencher

Originally a trencher was a wooden tray or stale piece of bread used as a plate, on which the food was placed before being eaten. A bowl of salt was placed near the trencher, and this became known as the trencher salt. Nowadays the word "trencher" is used to describe a type of salt bowl of flat open shape, usually without feet..

Tureen

Circular or oval, deep, covered bowl, used from the early 18th century for serving soup, sauce, vegetables or stew. As well as silver, tureens are also made in porcelain, pottery, and silver plate, Sauce tureens are smaller, plainer versions. The name derives from the French "terrine", meaning 'earthen vessel',

Vinaigrette

A vinaigrette is a small tightly-lidded box, usually finely worked in gold, silver or enamel, with an often elaborate pierced grate beneath the outler lid, with the interior holding a sponge soaked in aromatic vinegar, its purpose being to disguise odours caused by poor hygiene and drainage. Vinaigrettes were used from the late 18th century until the late 19th century.

To prevent corrosion by the vinegar, the interior of the vinaigrette was usually gilded. Occasionally the grille is made of gold, a rare and desirable feature although often difficult to distinguish from gilt.

They were usually rectangular in shape, but are found in other shapes iincluding fish, bells, helmets, beehives books and so on. The most common material used was silver, but they were also made in other materials including precious stone, shell, ivory, enamel, agate, pearl and combinations of these.

Among the most collectable are the silver vinaigrettes known as "castle-tops" where the lid has an embossed image of a topographical scene including a recognisable castle, abbey or country house.

One of the most prolific makers of vinaigrettes was Nathaniel Mills & Sons of Birminham, who specialised in all types of boxes including snuff boxes and card cases.

Wine Cooler (silver)

Silver, silverplate and Sheffield plate wine coolers (also known as ice buckets or ice pails) accomodate only one bottle and are designed to sit on the table, in contrast to the much larger timber versions which hold many bottles and sit on the floor.

Shapes vary from a plain bucket to a more elaborate vase or urn shape and often include an interior container to hold the ice and bottle, and handles to the side to assist on moving.

Most wine coolers were manufactured from around the 1770s to the Victorian period.

Wine Funnels

Wine funnells in silver, Sheffield plate and electroplate were mostly made between 1770 and 1820, their purpose being to remove sediment from wine decanted from the bottle to the decanter, or from the decanter to the glass.

Most wine funnels are one or two piece circular constructions with a fixed or removable strainer or gauze, or else an inner ring to hold a muslin straining cloth. They often also usually include a small hook on the rim.

Wine Labels

Popular with collectors, wine labels, also known as wine tickets, came into use in the 1730s. Early silver wine labels are likely to be escutcheon or shield shaped. Later labels were rectangular, eye-shaped, or crescent shaped. Silver labels of the 1820s onwards often feature vine leaves and tendrils. Enamel labels were also made from the 1750s, and these sometimes bear images as well as the name of the wine. Sheffield plate and electroplate were also utilised, as the materials came into use and less frequently, porcelain, ivory, tortoiseshell, mother-of-pearl, and bone. Labels bearing the names of unusual or unlikely wines are especially sought after, so the names of the more common wines may sometimes have been replaced by a more exotic wine.