Learn about antiques and collectables...

Click on a category below to show all the entries for that category.

Learn about and understand the items, manufacturers, designers and periods as well as the specialist terms used in describing antiques and collectables. Either click one of the letters below to list the items beginning with that letter, or click on a category on the left side of the screen to list the items under that category.

Albany Pattern

The Albany pattern is a design of sterling silver cutlery (silverware) that was popular in the 19th century. It is characterized by a simple, elegant design with a plain handle and a pointed tip. The pattern is named after Albany, New York, where it was first produced by the firm of Rogers, Smith & Co. in the 1850s. The Albany pattern is considered a classic design and is still popular today. It is typically used for formal occasions and is often paired with fine china and crystal.

Cake Basket

Popularly known as a cake basket, these baskets were probably also used for bread and fruit. They were introduced between 1730 and 1750, and at this time were usually oval in shape. Most cake baskets have a swing handle and pierced body. On important examples, the bottoms are engraved with armorials. Their popularity continued until the third quarter of the 19th century. Although oval shapes continued to be made, there were variations introduced and the designs became more flamboyant.

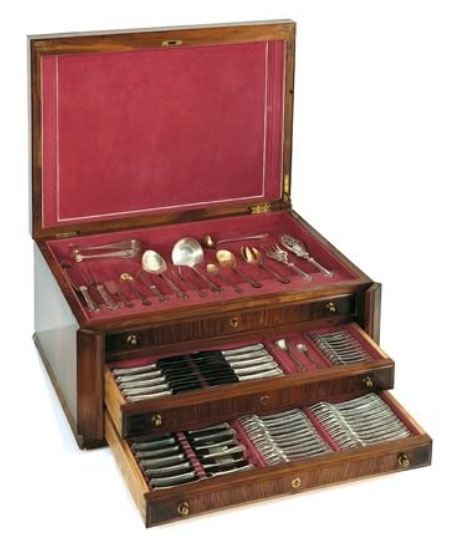

Canteen

A small cabinet, table or a box with drawers or lift out trays, for storing a set of cutlery.

Chafing Dish

A chafing dish is a type of portable heated tray or stand that is used to keep food warm during a meal or event. It is typically made of metal or stainless steel and has a shallow tray or pan for holding the food.

The tray is usually placed on top of a fuel burner, which generates heat to keep the food warm. Some chafing dishes also have a cover or lid to help retain heat and prevent contamination. Chafing dishes are often used at buffets, banquets, and other events where food is served and may need to be kept warm for an extended period of time.

Chatelaine

Originating in the 17th century as a device for suspending seals, by the late 18th century the chatelaine had evolved to become a major item of jewellery, worn from the waist, to which a variety of small implements, cases, and containers could be attached.

It took the form of a metal shield or plate fitted with a hook at the top to attach it to a belt, with a number of hooks at the bottom from which hung a number of short chains.

The objects attached to those chains covered the full gamut of household and personal activities and depending on the station of the wearer, could typically include about 4 to 6 from the following selection: sewing scissors, a scent bottle, keys, a spectacles case, a seal, a sovereign case, a vinaigrette, a vesta case, a pin holder, a snuff bottle, a tape measure, a thimble and a notebook.

Again depending on the station of the wearer , materials used included gold, sterling silver and silverplate.

Nowadays it is common for single items from the chatelaine to come onto the market.

Chocolate Pot

In 1521, during the conquest of Mexico, the Spanish conquistadors discovered cacao seeds, from which cocoa and cocoa butter, the basis for chocolate, are extracted. They took them back home to Spain, where new recipes were developed. About 100 years later, the drink spread throughout Europe and the Europeans began adding sugar and cream to their hot chocolate.

Chocolate pots were popular between about 1700 and 1800, and in style similar to a coffee pot , except that they included a small additonal secondary lid attached to the main lid, so that a rod called a molinet could be inserted into the pot to stir the chocolate before pouring. The handle is often set at right angles to the spout to facilitate pouring, and like a tea or coffee pot, may be insulated from the body of the pot.

Coaster

Coasters were intended to hold bottles or decanters of wine at the dinner table, and act as a recepticle to cash drips and ribbles on the foot of the wine container. As wine contains achohol, and residual liquid remaining on the base could damage the top of the table, more so if the table had a French polished surface. if the table had a cloth, the wine could leave a permanent stain.

On a table without a cloth, the felt base also allowed them to be slid from one guest to the next along the top of the table.

Made of silver or silverplate, they usually have a turned hardwood base, sometimes with a central silver boss, and usually covered in green baize on bottom.

The sides are usually cast or pierced, often with vine leaves, grapes and tendrils incororated into the design.

It is quite common for them to be available in pairs

Cream Jugs

The cream jug or milk jug was a component of most 18th and 19th century tea and coffee sets, but the numbers coming onto the market as single units, easily outnumber those being sold as part of a setting.

Silver cream jugs first appeared around 1700 as tea was becoming popular, following its introduction to Europe by the East India Company. The major ceramics manufacturers, such as Royal Doulton, Royal Crown Derby, Shelley, Royal Winton and Wedgwood all included a cream jug with their dinner and tea ware settings. Small jugs made by individual craftsman potters have also been labelled cream jugs, probably being the name most suitable for the size and style of the vessel.

Cream and milk jugs mostly have a pitcher shape, with a wide pouring spout and a baluster foot or three legs.

Cruet and Condiment and Sets

A cruet also known as a caster, is a small container to hold condiments such as oil, vinegar, mustard, pepper. Its shape and adornments will depend on the specific condiment for which it is designed. For example a cruet for liquids may have a jug-like shape, while a cruet for a spice may be cylindrical with a lid and perhaps a small spoon for serving.

Cruets were made in silver, silver plate, ceramic and glass, and sometimes a combination of two materials, usually as a glass body with a silver or silver plated top.

The earliest cruets, from the beginning of the 18th century were known as "Warwick cruets" after a cruet set made by Anthony Nelme in 1715 for the Duke of Warwick, and include three elaborately decorated and shaped matching silver casters, usually with one unpierced, which held powdered mustard, and the other two for oil and vinegar, combined in a stand with a handle enabling it to be passed between dinner guests.

In the Victorian era with more elaborate dining settings, the number of condiments used during a meal increased, as did the number of containers in the cruet set, and some cruet sets contained up to six or eight containers, either arranged tw-by-two, or in a circular container. Glass bottles replaced the silver containers of the earlier era and the holders became simpler, sometimes being a metal frame attached to the base.

Completeness and originality is important when purchasing a cruet set, and missing containers, replaced containers and missing or chipped stoppers will depreciate the value of a cruet set.

Another type of cruet set is an egg cruet, typically consisting of four to eight egg cups in a stand, often with a spoon for each egg cup. These were mainly made in silver or silver plate, and occasionally ceramic. The egg cups may fit in rings, or over a stud on the base of the stand. Sometimes the interiors of the egg cups are gilded to prevent corrosion. The stands are either solid, or a framework with a handle.

Dish Rings

Dish rings were in use between about 1750 and 1800, and were designed to protect the table or sideboard surface from damage from a hot dish. They are usually about were mosty made in silver, and to a lesser extent Sheffield plate, of circular in shape with pierced, embossed and chased decoration to the in-curved side, the piercing also allowing the heat to escape.

They are also known as potato rings, probably in deference to their supposed Irish origins.

Manufacture of dish rings was revived in the late 19th century for several decades.

Elkington & Co.

Elkington & Co. was a Birmingham silverware company producing fine silverware and silver plate. The business was founded in 1815, by the uncle of George Richards Elkington (1801-65). On his uncle's death George Richards Elkington became the sole proprietor and took in his brother Henry Elkington as a partner, changing the name to G. R. Elkington & Co. The business took out patents for the plating of articles in 1836, 1838 and 1840. In 1842 a third partner, Josiah Mason, joined the firm and the name was changed to Elkington, Mason, & Co. until 1861, when the partnership with Mason was terminated.

The greater durability of electroplate together with its affordability meant that it steadily ousted pure silverware, especially for the more functional items such as tea and coffee services. The company licenced the process to a number of manufacturers, including Christofle & Cie of France.

By 1880 the company employed over 1000 workers at premises in Birmingham, and had a further 6 works.

The company received awards at the great international exhibitions from the 1850s onwards for its excellence in artistic quality and fine design and held Royal Warrants from British Royalty including Queen Victoria, King Edward VII, Queen Alexandra, King George V, Queen Mary and King George VI. Elkington & Co. supplied plated wares to the luxury dining sections on board the Titanic and other ships in the White Star Line fleet.

By 1900 the Elkington monopoly of electroplate diminished as the original patent rights expired, and this period witnessed the enormous increase in output of other Birmingham, London and Sheffield manufacturers.

The firm operated as Elkington & Co. from 1861 until 1963 when it was acquired by British Silverware Ltd. which also had the Mappin & Webb brand. During World War II the company had stopped producing plated wares, and moved into copper refining which continued when it became a subsidiary of Delta Metals Group in 1955.

The original Elkington Silver Electroplating Works, in Newhall Street in Birmingham, became the Birmingham Science Museum in 1951, until its closure in 1997.

Entree Dishes

The name would indicate that entree dishes were designed to serve the course before the main course.

However they are also called "serving dishes" which is probably more indicative of their purpose: to hold and serve the vegetables accompanying the meat, or to hold the hot accompaniments for a breakfast. In order to keep the contents of the dish warm, many entree dishes had an inlet and double skinned base so that hot water could be added to the lower section of the dish. Another feature of theses dishes is the detachable top handle, allowing the dish itself to be heated in the oven or on the stove, with the unheated handle added after the hot dish was removed from the heat.

They became popular in the late 18th century, and were often made in pairs or fours. When owned by an important family, the family's armourials were often engraved on the lid.

Ep / Epns

The abbreviation for electroplated and electroplated nickel silver, that is, silver plate.

The body of the piece is made of a common metal such as copper, and electroplating involves placing an extremely thin layer of silver on the surface of the piece. The resulting silver content is very small.

Unlike solid silver items, there is minimal underlying scrap value, and the value of such pieces is based on the quality, design and construction of the piece.

Epergne

A table centrepiece, which may have a large central bowl or dish, and a series of smaller bowls suspended from a central stem or branches, with the smaller bowls used to display sweetmeats. Some of the grander examples were made in silver, but epergnes were also made in ceramic and glass.

Fish Servers and Slices

The fish slice dates from about the 1750s, and was popular until the late Victorian period. made of silver or silver plate, they were designed for serving fish at the table, and usually had a wide scimitar shaped blade, often pierced and engraved with a flat or decorative cast handle.

Some fish slices had a marine decoration to the blade or handle representing fish, eels or shrimps.

During the Victorian period, they were popular as a gift presented in a boxed set with the addition of a wide bladed matching fork, and were then called fish servers.

Husk Motif

The husk motif is a decorative element that has been used in furniture, silver, glass and ceramics decoration for centuries. The motif is typically based on the shape of the husk, or outer covering, of a nut or seed. It is often depicted as a series of overlapping, scalloped shells that create a textured, ornamental pattern.

In furniture, the husk motif is commonly used in the design of chair and table legs, as well as in the decoration of cabinet doors and drawer fronts. The motif is carved into the wood or other material, creating a three-dimensional effect that adds depth and visual interest to the piece.

In ceramics, the husk motif is used in a variety of ways, from the decoration of bowls and plates to the design of decorative tiles and other objects. The motif is often painted or carved into the surface of the clay, creating a relief pattern that adds texture and dimensionality to the piece.

The husk motif has been used in many different historical and cultural contexts, from ancient Greece and Rome to 18th-century France and England. It has been adapted and modified over time, with variations including the acanthus leaf and the palmette motif.

Kettles on Stand

Unlike the utilitarian copper kettles found in the kitchen, these fancy kettles were an indispensable accessory for the formal tea party, held in the parlour or sitting room. Also known as spirit kettles, they were popular during the whole of the 18th and 19th centuries, and were originally used for replenishing the teapot.

They were sometimes one of the components of a tea set, but most examples appearing on the market in Australia are singles.

Most stands had four legs, with the burner situated at mid height between the four legs, allowing the presence or otherwise of a flame to be seen. Some kettles were attached to the stand with a chain, secured by a removable locking pin. The burners were removable from the frame for cleaning purposes

Loaded

In silverware the hollow part of the object, such as the stem of a candlestick or the handle of a knife, that has been filled (loaded) with pitch or sand to add additional weight for stability.

Marrow Spoon

A spoon with a long handle and a narrow scoop shaped bowl, used to scoop and eat marrow from the hollow centre of roasted bones. Some marrow scoops are double ended with a different shaped bowl at each end.

Meat Covers

Meat covers, also known as dish covers, were designed for covering large platters in order to protect the food and retain the heat. They are usually ovel, matching the typical shape of tha platter, and vary in size from about 30 cm to 60 cm. They are topped by a reeded or foliate handle. While the surface of most are solid metal, there are examples where the outer surface is wholly or partly plated wire mesh.

The covers were made in silver, Sheffield plate and silver plate and earlier silver examples date from the mid 1700s. Due to the amount of silver they contain, and consequently their cost, and value if sold for melt, silver covers are vastly outnumbered by plated examples. Sheffield plated examples date from the early 1800s while plated covers are generally from the Victorian era.

Muffineer

A muffineer is a

small container with a pierced top, usually of of silver, or silver plate. It gained

its name from its early use for sprinkling sugar or cinnamon on muffins. muffineer

were part of the Victorian tableware. After the First World War.

Old English Pattern

The Old English pattern as is commonly seen on silver flatware is characterized by a simple, clean shape with a slightly upturned tip and a broad handle that tapers gently towards the bowl or blade. The handle may be plain or decorated with a subtle design, such as a line or ridge along the edge or a small decorative motif at the tip. This pattern was first introduced in the 18th century and has remained popular ever since, making it a popular choice for traditional and formal table settings.

Onslow Pattern

The Onslow pattern is a design commonly found in silver and silver plated flatware. It is a highly decorative pattern that features a shell motif on the handle, which is often accompanied by scrolls, flowers, and other ornate designs. The Onslow pattern was first introduced in the mid-18th century and has remained a popular choice for flatware enthusiasts throughout the years. The design is named after Arthur Onslow, who served as the Speaker of the House of Commons in England from 1728 to 1761. It is said that Onslow was a great lover of fine silver and that the Onslow pattern was created in his honour.

Sauce Boat

Sauce boats, also called gravy boats, are a small jug form object used for serving sauces and gravy as indicated by the name. They were made in silver, silver plate or ceramics became fashionable in the early 18th century. Early suaceboats were usually plain and of oval shape, with a solid oval foot.. In the later Georgian period they became more elaborate, with the metal examples decorated with chasing and engraving, and a three-footed base, and sometimes available in pairs. Ceramic suaceboats were often part of a dinner service, and some of the ceramic sauceboats have an attached plate, its purpose being to catch drips and dribbles.

Scallop / Shell Motif

The shell motif has been used in furniture and decorative arts for centuries. In ancient Greece and Rome, shells were often used as decorative elements on furniture and in mosaics. The scallop or cockleshell are the most commonly used. During the Renaissance, the shell motif became popular in furniture and architecture, as the ornate decoration was seen as a symbol of wealth and luxury. In the 18th century, the Rococo style of furniture and decorative arts featured an abundance of shell motifs, and it was used by Thomas Chippendale and as a feature on Queen Anne style cabriole legs. In the 19th century, the shell motif was incorporated into Victorian furniture and decorative items, and often a representation of the the conch shell was inlaid into furniture.

Sheffield Plate

Sheffield Plate was the first commercially viable method of plating metal with silver. The method of plating was invented by Thomas Boulsover, a Sheffield Cutler, in 1743 and involved sandwiching an ingot of copper between two plates of silver, tightly binding it with wire, heating it in a furnace and then milling it out in to sheet, from which objects could be made.

Originally used by its inventor to make buttons, the potential of the material was quickly realised, and soon it was being used to fashion boxes, salvers and jugs, and not long after that candlesticks and coffee pots, and other traditional tableware.

Although there was a considerable saving in the amount of silver used, Old Sheffield Plate manufacture was more labour intensive than solid silver, meaning higher labour costs. This meant that Old Sheffield Plate was very much a luxury product, and only available to the very wealthy.

The thickness of the silver means that many 18th century Sheffield Plate pieces still have a good layer of silver, while electroplated pieces (EPNS), may have been replated several times over their lifetime. Where the silver has worn off the Sheffield Plate the soft glow of the copper base can be seen underneath. However this is not an infallible guide that the piece is Sheffield Plate, as many EPNS items were also plated on to a copper base.

Most Sheffield Plate items are unmarked, whereas most elecroplated items display manufacturers names or marks, quality indications such as "A1", "EP", together with pattern or model numbers.

Sheffield Plate

Sheffield plate was the first commercially viable method of plating metal with silver. The method of plating was invented by Thomas Boulsover, a Sheffield Cutler, in 1743 and involved sandwiching an ingot of copper between two plates of silver, tightly binding it with wire, heating it in a furnace and then milling it out in to sheet, from which objects could be made.

Originally used by its inventor to make buttons, the potential of the material was quickly realised, and soon it was being used to fashion boxes, salvers and jugs, and not long after that candlesticks and coffee pots, and other traditional tableware.

Although there was a considerable saving in the amount of silver used, Old Sheffield Plate manufacture was more labour intensive than solid silver, meaning higher labour costs. This meant that Old Sheffield Plate was very much a luxury product, and only available to the very wealthy.

The thickness of the silver means that many 18th century Sheffield Plate pieces still have a good layer of silver, while electroplated pieces (EPNS), may have been replated several times over their lifetime. Where the silver has worn off the Sheffield plate the soft glow of the copper base can be seen underneath. However this is not an infallible guide that the piece is Sheffield Plate, as many EPNS items were also plated on to a copper base.

Most Sheffield plate items are unmarked, whereas most elecroplated items display manufacturers names or marks, quality indications such as "A1", "EP", together with pattern or model numbers.

Sheffield plate was made commercially between 1750 and 1850.

Snuffer

A device for extinguishing a candle, usually made of silver or silver plate, and sometimes ceramic.

There are two types, the first in the shape of a cone that is placed over the the top of candle and smothers the flame, also known as an extinguisher. The cone shaped snuffer may be part of a candlestick or have its own stand. The second type is similar to a pair of scissors with a small box on one of the blades into which the wick falls when it is cut.

Prior to the invention of snuffless candles in the 1820s, this type of snuffer was used to trim the wick of the tallow candles (also called "snuffing") that were in use at that time, so that they did not become too long. With the snuffles candle, the newly developed plaited wick bent into the flame as it burnt, and was fully consumed.

This type sometimes comes with an accompanying stand or tray.

However the two components may have been separated, and a new name found for the snuffer tray, such as a pen tray.

Stokes (australasia) Ltd

Thomas Stokes a diesinker and electroplater was born in Birmingham in 1831, and arrived in Victoria in the 1850s, to join the search for gold. Soon after, presumably being unsuccessful in his quest or gold he established a business in Melbourne as a “Die Sinker and Medallist, Stamper and Token Maker”, and soon after added electroplating to the services he was able to supply.

By the 1880s he was employing 30 tradesmen and apprentices. The company's specialty was badges and at about this time they were producing coat and collar badges for schools, colleges, lodges and associations, the Victorian Railways, Salvation Army and the Australian Army. The business became a proprietary concern in 1911, re-named Stokes & Son Pty Ltd., and in 1962 Stokes became a public company, renamed Stokes (Australasia) Ltd

In the 1950s the company diversified into manufacturing components for the automotive and domestic appliance industries, and became one of Australia's leading suppliers to these industries.

Today, Stokes is a publicly listed company, with offices and representatives throughout Australia, Asia and the Pacific. As well as being the Australia's leading independent distributor of appliance spare parts, the industry leader in the supply of badges, medallions and associated products it is also the country's major manufacturer of electrical elements.

Tankard

A tankard is a drinking vessel for beer, ale, and cider, similar in shape to a large mug, and usually with a hinged lid. Silver tankards were in use in Britain and other parts of Europe from at least the sixteenth century, pewter tankards probably from the thirteenth. In the 19th century a number of ornately carved ivory tankards were produced, but these were designed to demonstrate the skill of the carver, rather than for day to day use. The shapes of tankards vary, sometimes globular, sometimes a tapering concave. For those with lids, the lid usually includes a thumbpiece that the drinker can hold down to keep the lid open. Variation in the design of the thumbpiece include wedge, ball and wedge, ball, hammer head, bud and wedge, double volute (scroll), chair-back, ball and bar, shell, double acorn, corkscrew, and ram's horn.

Wine Cooler (silver)

Silver, silverplate and Sheffield plate wine coolers (also known as ice buckets or ice pails) accomodate only one bottle and are designed to sit on the table, in contrast to the much larger timber versions which hold many bottles and sit on the floor.

Shapes vary from a plain bucket to a more elaborate vase or urn shape and often include an interior container to hold the ice and bottle, and handles to the side to assist on moving.

Most wine coolers were manufactured from around the 1770s to the Victorian period.

Wine Funnels

Wine funnells in silver, Sheffield plate and electroplate were mostly made between 1770 and 1820, their purpose being to remove sediment from wine decanted from the bottle to the decanter, or from the decanter to the glass.

Most wine funnels are one or two piece circular constructions with a fixed or removable strainer or gauze, or else an inner ring to hold a muslin straining cloth. They often also usually include a small hook on the rim.